Home

Resistance Within Germany

Resistance of German Aristocracy

1938 - First Coup Attempt

1942 - Plan Valkyrie

1943 - The "Perfect" Assassination Attempt

July 15, 1944

July 20, 1944

General Friedrich Olbricht

An Obsolete Honor

Hitler's Demons-Kindle Edition

Codename Valkyrie

Allies Response to Germany's Resistance

Hitler's Popularity

Sources - Further

Reading

German Army Military Ranks

Glossary

Biography

Links

Web Rings

Awards

Guest Book

Author Site

Author's Blog

Resistance Within Germany

Resistance of German Aristocracy

1938 - First Coup Attempt

1942 - Plan Valkyrie

1943 - The "Perfect" Assassination Attempt

July 15, 1944

July 20, 1944

General Friedrich Olbricht

An Obsolete Honor

Hitler's Demons-Kindle Edition

Author

Interview

Valkyrie Teacher Supplement and Discussion Guide

Readers View Review

Midwest Book Review

Historical Novel Society Review

Kay's Bookshelf Review

Video Trailer of book

Valkyrie Teacher Supplement and Discussion Guide

Readers View Review

Midwest Book Review

Historical Novel Society Review

Kay's Bookshelf Review

Video Trailer of book

Codename Valkyrie

Allies Response to Germany's Resistance

Hitler's Popularity

Sources - Further

Reading

German Army Military Ranks

Glossary

Biography

Links

Web Rings

Awards

Guest Book

Author Site

Author's Blog

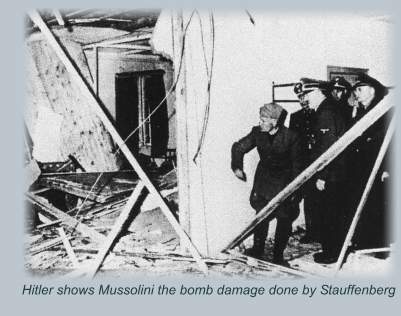

| 20 July 1944: The Final Throw of the Dice The Attempt to Free Germany of Hitler and His Regime Early on the morning of 20 July 1944 Stauffenberg again flew to Hitler's HQ in East Prussia with the intention of killing Hitler. Nearly all the principle conspirators were informed about the imminent assassination attempt and warned to be on the alert to fulfill their assigned roles. Since the briefing at which Stauffenberg would have the opportunity to set off his bomb was scheduled for 13.00, no one expected any thing to happen before that time. In the Wolfschanze, however, the daily briefing was moved forward by half an hour due to the expected arrival of Mussolini. Stauffenberg activated the fuses on the bomb in one of his briefcases, placed this bomb under the briefing table close to where Hitler was standing and then slipped out of the briefing hut on the pretext of making a phone call. Shortly after 12.40 an explosion took place. Stauffenberg immediately bluffed his way past the guards controlling the lock down of Hitler's HQs. He made it aboard the waiting aircraft and took off, just moments before all aircraft at the field were grounded. He had succeeded in detonating a bomb in the room where Hitler was standing and in escaping the Wolfschanze with his life, but he had had no opportunity to telephone with Berlin. He was incommunicado until he landed. General Fellgiebel, the man responsible for informing Olbricht about a successful assassination and then cutting Hitler's HQ off from the outside world, however, learned what Stauffenberg had not waited to find out: that Hitler had survived the blast. When Fellgiebel tried to pass this word on to the conspirators in Berlin, he discovered that someone else, the Deputy Commander of Hitler's HQ, had already taken control of all communications to and from the Wolfschanze. Thus, it was not until 15.00 that the first news of an "incident" at Hitler's HQs reached the Bendlerstrasse. Olbricht requested more information and at about 15.30 was informed that an explosion had taken place in which several officers were severely injured. According to one version of events the cryptic message passed to Olbricht by his fellow-conspirator General Fellgiebel was: "Something terrible has happened. The Führer lives!" In short, the only thing that was clear to Olbricht by 15.30 on the afternoon of 20 July 1944 was that the assassination had failed. It was not clear, whether Stauffenberg had been killed in his own attempt or had survived the blast only to be arrested. This put Olbricht in a terrible dilemma. After all, if Stauffenberg had blown himself up in some kind of accident, it would have been madness to set the coup in motion knowing Hitler was still alive. In such a situation, the coup might still have had a chance at a latter date with a different assassin.  Shortly

before 16.00, Stauffenberg and his adjutant landed at an airfield on

the outskirts of Berlin and put a call through to Olbricht, in which

Stauffenberg announced to Olbricht that Hitler was dead. Olbricht

went immediately to the C-in-C of the Home Army, Generaloberst

Fromm, to try to persuade him, the only man authorized to issue

"Valkyrie" in the event of Hitler's death, to do exactly that.

Had Hitler been dead, Fromm might very well have done so, but Fromm was

skeptical. He insisted on proof of Hitler's demise. Olbricht

– trusting Stauffenberg's word – himself picked up the

phone and put through a call to GFM von Keitel. Keitel, however,

emphatically denied that Hitler had been killed. Fromm

consequently refused to issue "Valkyrie." So Olbricht and his

staff issued the orders illegally for a second time. Shortly

before 16.00, Stauffenberg and his adjutant landed at an airfield on

the outskirts of Berlin and put a call through to Olbricht, in which

Stauffenberg announced to Olbricht that Hitler was dead. Olbricht

went immediately to the C-in-C of the Home Army, Generaloberst

Fromm, to try to persuade him, the only man authorized to issue

"Valkyrie" in the event of Hitler's death, to do exactly that.

Had Hitler been dead, Fromm might very well have done so, but Fromm was

skeptical. He insisted on proof of Hitler's demise. Olbricht

– trusting Stauffenberg's word – himself picked up the

phone and put through a call to GFM von Keitel. Keitel, however,

emphatically denied that Hitler had been killed. Fromm

consequently refused to issue "Valkyrie." So Olbricht and his

staff issued the orders illegally for a second time.Between 16.30 and 16.45 Stauffenberg arrived back at the Headquarters of the Home Army. He reported at once to Olbricht and again - euphorically - insisted that Hitler was dead. Obviously, this was not true, but one must try to put oneself in Stauffenberg's shoes: after two unsuccessful assassination attempts, he had finally succeeded in detonating a bomb in Hitler's immediate vicinity and then, under highly dramatic circumstances, escaped alive. Stauffenberg honestly didn't know that Hitler had survived the blast. Nor did he know that Fellgiebel had failed to close down communications from OKW and that hence the entire Nazi apparatus was still fully functional. Stauffenberg went with Olbricht to try to persuade Fromm to issue Valkyrie over his signature. A heated argument ensued in which Stauffenberg claimed, completely fancifully, to have personally seen Hitler's body carried out of the briefing hut. Olbricht then informed Fromm that "Valkyrie" had already been issued. Stauffenberg furthermore admitted that he had himself set off the bomb – to which Fromm replied that in that case he ought to shoot himself at once. Stauffenberg refused, and Olbricht confessed his complicity in the plot. According to Fromm (the only man involved in this confrontation to survive long enough to be interrogated by the Gestapo) he told Olbricht he was under arrest, to which Olbricht replied that Fromm had mistaken the situation. Two junior officers loyal to the conspirators were called and entered the office with drawn pistols. They detained Fromm under guard, while General Hoepner (as planned by the conspirators) took over Fromm's office and position. The anti-Nazi Hoepner at once started issuing orders as "Commander-in-Chief" of the Home Army. After this, the entire coup appeared to go according to plan. Olbricht and Stauffenrberg went to work telephoning with key offices and commands, informing them of the situation, and generally driving the coup forward. They answered questions and countered doubts voiced by both the initiated and the uninitiated. One after another of the subordinate commands received and started carrying out the illegally issued orders.  But Hitler was not dead. Furthermore, the conspirators at his HQ had been unable to cut off the Wolfschanze

from the outside world, and hence Hitler's entire staff, OKW, was fully

operational. This meant that any commander who couldn't or didn't

want to believe that Hitler was dead, could contact the Wolfschanze

requesting confirmation or details. Hitler's staff, that had

initially assumed that the assassination was the act of a lone man,

gradually grasped that in fact a coup was in progress in Berlin. But Hitler was not dead. Furthermore, the conspirators at his HQ had been unable to cut off the Wolfschanze

from the outside world, and hence Hitler's entire staff, OKW, was fully

operational. This meant that any commander who couldn't or didn't

want to believe that Hitler was dead, could contact the Wolfschanze

requesting confirmation or details. Hitler's staff, that had

initially assumed that the assassination was the act of a lone man,

gradually grasped that in fact a coup was in progress in Berlin. At roughly 18.00 the first counter-orders went out from OKW. Keitel ordered that all orders signed by Fromm, Witzleben and Hoepner were null and void. Furthermore, a public announcement was made over the radio informing the German people that an assassination attempt had been made, but that it had failed. Now the first calls started to come into the Bendlerstrasse from confused subordinate commands where two, contradictory sets of orders had been received. Olbricht and Stauffenberg tried to convince all these callers that the orders from OKW were the machinations of the SS in an effort to retain control of the state. The Army, Olbricht and Stauffenberg assured the military commanders, was taking over now that Hitler was dead. The implication was that the Army was finally "cleaning up" – something very many military men welcomed and supported whether they were part of the conspiracy or not. In short, as long as the situation remained unclear, the conspirators enjoyed a surprising degree of success. But gradually doubts grew. People started to ask themselves "what if Hitler is still alive?" Clearly, if he were dead, there was no harm in "following orders," but if he were alive and they followed the wrong orders it would mean arrest, possibly torture, and death. Under these circumstances, when officers were confronted with two sets of contradictory orders, the political sentiments of the individual became decisive. A comparison between the response to the orders in Paris and Military District II is particularly telling.  In

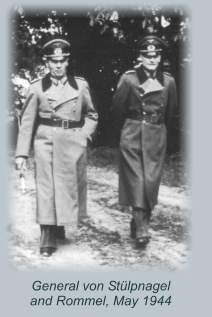

Paris, where the Military Governor, General von Stülpnagel, was an

opponent of Hitler's going back to the September Conspiracy of 1938,

the orders from the Bendlerstrasse were followed willingly and with

alacrity. In Military District II, where the commander was not a

conspirator, he could not bring himself to follow the "Valkyrie" orders

because these were "clearly treasonous" – even though he admitted

that "with his heart" he was on their side. In

Paris, where the Military Governor, General von Stülpnagel, was an

opponent of Hitler's going back to the September Conspiracy of 1938,

the orders from the Bendlerstrasse were followed willingly and with

alacrity. In Military District II, where the commander was not a

conspirator, he could not bring himself to follow the "Valkyrie" orders

because these were "clearly treasonous" – even though he admitted

that "with his heart" he was on their side. Likewise in Berlin, it was the certainty of Hitler's survival that turned the tide against the conspirators. Most spectacularly, the always suspect (from the conspiracy's perspective) commander of the "Grossdeutschland Batallion," the unit responsible for sealing off the government district of Berlin, turned against the conspiracy - but only after speaking with Hitler personally. Major Remer first carried out his military orders meticulously. Goebbels, however, put a call through to the Wolfschanze, demanded to speak to Hitler personally, and then handed the receiver over to the awestruck major. Major Remer became Hitler's ardent supporter at once. Hitler personally promoted him two ranks and ordered him to crush the coup with his troops. From one minute to the next Remer went from keeping guard on the Propaganda Ministry to being the man determined to put down the coup. Had the conspiracy succeeded in a having one of their own – say Axel von dem Bussche – in command of the "Grossdeutschland Batallion" on 20 July 1944, maybe even Hitler's survival would have been immaterial. But for the vast majority of German officers – just as GFM v. Kluge had foreseen back in early 1943 – Hitler's death was the absolute prerequisite for action against the regime. Even in the Bendlerstrasse itself, the increasing certainty that Hitler was alive eroded the support that Olbricht and Stauffenberg had initially enjoyed among their respective staffs. Several officers of GAO decided it was time to go to General Olbricht and find out directly from him what was going on. They confronted Olbricht at around 22.30 - fully armed since they had been asked to take over guard-duty. As these officers assured me personally, they did not come in with pistols drawn and they did not threaten General Olbricht. They still trusted him, but they no longer believed that they had been told the whole truth. At this inopportune moment, Stauffenberg sought Olbricht out. Seeing the other officers with their weapons, he decided to flee. One of the officers shouted after Stauffenberg, ordering him to halt. Stauffenberg did not. Shots were fired. Stauffenberg was wounded.  Olbricht

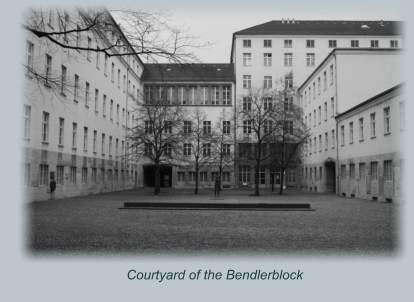

was now arrested and escorted by several of these staff officers to

where Fromm was still being held in custody by junior officers loyal to

the conspiracy. Fromm was released and immediately ordered the

known conspirators – Beck, Olbricht, Stauffenberg, and two others

- arrested. Without the slightest adherence to legal niceties, he

summarily found them guilty of High Treason and sentenced them to

death. Beck asked permission to shoot himself, and was granted

this right. Meanwhile, the other four officers were taken down the

winding, red-marble stairway from the GAO into the courtyard of the

Bendlerstrasse. A firing squad was hastily improvised and the

south wall of the courtyard was lit by the headlights of staff cars.

The first four conspirators, Friedrich Olbricht, Claus Graf

Stauffenberg, Albrecht Ritter Mertz von Quirnheim and Werner von

Haeften, were shot shortly after midnight. More than 5,000 other

conspirators and sympathizers followed them to an untimely death in the

months to come. The attempt to free Germany of the Nazis from

within had failed. Olbricht

was now arrested and escorted by several of these staff officers to

where Fromm was still being held in custody by junior officers loyal to

the conspiracy. Fromm was released and immediately ordered the

known conspirators – Beck, Olbricht, Stauffenberg, and two others

- arrested. Without the slightest adherence to legal niceties, he

summarily found them guilty of High Treason and sentenced them to

death. Beck asked permission to shoot himself, and was granted

this right. Meanwhile, the other four officers were taken down the

winding, red-marble stairway from the GAO into the courtyard of the

Bendlerstrasse. A firing squad was hastily improvised and the

south wall of the courtyard was lit by the headlights of staff cars.

The first four conspirators, Friedrich Olbricht, Claus Graf

Stauffenberg, Albrecht Ritter Mertz von Quirnheim and Werner von

Haeften, were shot shortly after midnight. More than 5,000 other

conspirators and sympathizers followed them to an untimely death in the

months to come. The attempt to free Germany of the Nazis from

within had failed.

|

||||

ONLINE TRANSLATOR AND DICTIONARY

PRIVACY I COPYRIGHT I CITING I SITE MAP

Contents of this web site are copyrighted. ©1993-2012 Helena P. Schrader unless otherwise noted.

If you would like to use the material of this site, please contact Helena Schrader.

If you experience any problems with this site, please contact the web mistress.